You’ve been learning things wrong your whole life.

There – I’ve said it.

The conventional approach to learning is to focus intently on one small area and not budge until it has been mastered. It just seems the most logical way.

I remember trying to learn the G major scale by focusing on just the Ionian mode. I must have spent a week in this one position… trying to play it up and down perfectly. No wonder it took me several weeks to learn the whole scale – and even then, I would forget half of the notes.

If I had used the three methods I’m about to reveal to you, I reckon I would have learnt the entire scale, in a variety of keys and positions, in half the time.

What is this sorcery – I hear you cry.

Gather around, for I’m about to reveal all…

The interleaving approach

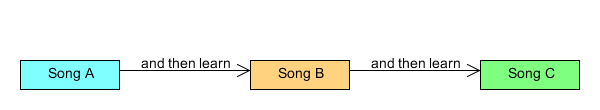

As I stated above – when presented with several different tasks or disciplines, most people would try and narrow down their focus by selecting just one area and mastering it before moving on to the next. This learning strategy is extremely common and it’s probably something you’ve done throughout your life without even realising.

It just seems the most logical method. Here’s a real world example of what I’m talking about.

A guitarist, let’s call him Boris, plans on learning three new songs to add to his repertoire. They are ‘Sweet Home Alabama’, ‘Tears in Heaven’ and ‘Master of Puppets’. Three completely different songs, each with specific techniques not found in the other two.

Intuition tells Boris that because he hasn’t been playing for very long, it’s a good idea to pick the easiest of the three and stick with it until he’s fairly happy he can play it to a decent standard.

Once this has been achieved, common sense tells him to move on to the next one before finally, tackling the 8 and a half minute thrash fest that is Master of Puppets.

Boris is making a big mistake.

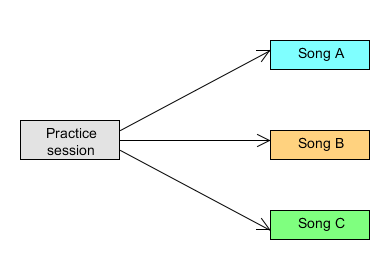

Robert Bjork, director of the UCLA Learning and Forgetting Lab, has forged a career on devising strategies for memory retrieval, and according to Bjork, the better option would be to interleave between all three songs during the same practice session. Maybe spending 1 hour with each song rather than spending 3 hours focusing on one specific song or technique.

Here is why.

When we focus on one specific task at the expense of other similar tasks, our brain is tricking us into believing we are getting better when in reality, all we are doing is improving our rote memory. We are memorising the information without developing the underlying understanding of what we are supposed to be learning.

This false confidence gives us positive feedback and we’re encouraged to continue along the path we have set out for ourselves. Whereas, if we interleave between several different tasks, we get the impression the information isn’t sinking in. The immediate positive feedback isn’t there, so we become disheartened and may even lose confidence in ourselves.

But here’s the thing.

Instead of making a giant leap in perceived ability following an hour of learning one song, or technique; interleaving would allow Boris to take smaller, almost imperceptible steps forwards in all three songs and a multitude of techniques. Over a period of time, the sum of these small improvements would be greater than if he locked down his focus on just the one ‘blocked’ area.

Here are some other examples.

- If you want to improve your tennis serve, instead of spending the entire practice session on this one technique; split up your time equally on serving, forehand, backhand, volleying and footwork. The skills gained in these other areas will indirectly aid your serving ability with the added benefit of improving your all round game.

- If you want to improve your listening comprehension in French, don’t spend your study time listening to every piece of audio you can get your hands on; divide this time up on learning vocabulary, speak the phrases you already know, write these down afterwards and read several pieces of text. The more words you recognise and use, the easier it will be to pick them out by ear.

- If you’re looking to create a lean, yet muscular physique, it’s not worth the effort to yo-yo between 6 months of bulking up followed by 6 months of cutting the fat. It’s healthier and you’ll receive greater long term benefits if you work on gaining muscle and leaning out at the same time. Eat slightly more calories on workout days and slightly less on rest days. You won’t notice the change on a day to day basis, but over several months you’ll look better than ever.

Spacing – The art of forgetting everything you know… but not quite

At some point in our lives, we’ve all attempted to counter the terror of an exam by staying up all night, cramming as much information into our tired brains as possible and hoping we can somehow blag our way into achieving a half way decent grade.

This ‘mass presentation’ works unbelievably well for short term memory recall, but as for committing something to long term memory, it’s next to useless.

But there is a different approach, and this involves ‘spacing’ our learning by finding this information repeatedly over spaced intervals.

Come here Boris; we need you again.

Boris is currently studying for an upcoming maths exam – it’s not all fun and guitars you know. He’s not only deeply upset about these studying sessions keeping him away from his beloved axe; Boris is also having trouble remembering how to solve algebraic equations.

They’re just not sinking in. He does the exercises, reads the tutorial notes and attends every lecture, but after a week or two, he forgets everything. If only there was a technique to help him out…

As luck would have it; this is where spaced repetitions can save the day.

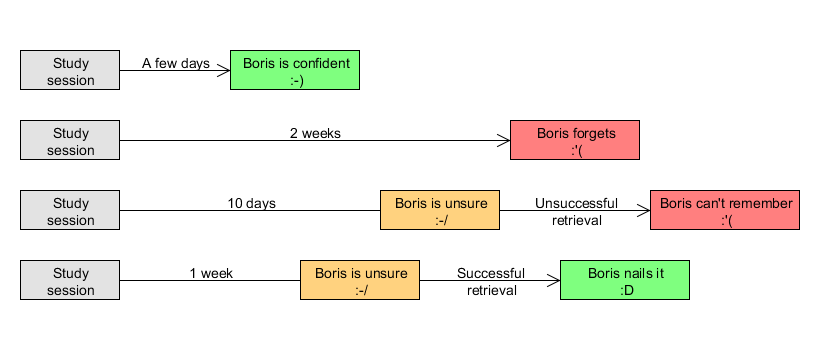

This method is all about timing. A less is more approach to learning that will appeal to the procrastinators out there who regularly put off their study sessions in favour of doing absolutely nothing.

It works like this;

After we’re first exposed to a piece of information, the length of time between study sessions is crucial in terms of the learning speed. If this time is too short (as in cramming) then the benefits are only useful in the short term, but if a longer duration of time is used, successfully retrieving the information will help us cement this knowledge in the long run. But here’s the catch; this only works if our retrieval is successful. If the duration of time is too great, and we can’t remember enough to work with, then the spaced repetition method will fail.

Annoyingly, the tougher it is to remember, the quicker the retrieved information is committed to our long term memory. By reducing the accessibility of the information we enhance the learning potential of this information. Counter intuitive 101.

It’s a fine line, but when done correctly, it’s one of the most reliable methods of learning ever tested. It works with everything from studying for exams, remembering random nonsensical words and even language acquisition.

Here some real world examples of spacing in action;

- Regularly test yourself by taking quizzes, online tests and any past papers you can get your hands on when preparing for an upcoming exam. Finish the bulk of your revision several weeks before the exam date, and train your brain to retrieve the information by testing yourself at weekly intervals in the lead up to the big day. Testing is a ‘desirable difficulty’ which gives the illusion of not helping you learn; when in fact it is actually more efficient than studying for seeking long term improvement.

- If you’re trying to remember how to play a song on a musical instrument; resist the temptation to look at the sheet music. Doing so will only give you a short term boost in performance. To improve your chances of committing this piece to long term memory – figure it out yourself. Apply this technique to every riff, melody or scale pattern you’re unsure of and it’s unlikely you will ever forget it again.

Deliberate practice is the key to success

The third learning technique in this article slightly contradicts the concept of interleaving by focusing on deliberate practice – which can be thought of as ‘chunking’.

Well, it is and it isn’t. To save any confusion, I better explain what is meant by deliberate practice (and it’s something you should do regardless).

You’ve all heard of the 10,000 rule, right? To reach a level of mastery one must study or practice a skill for at least 10,000 hours, yada yada yada…

For the most part, it’s accurate, to an extent. The problem is interpretation. If something is posted online or published in a book there is a high probability that someone stupid will read it, misinterpret it, and then spread it as some form of under evolved Chinese whisper of lies and mass confusion.

Everyone laps it up, and then proceeds to fail miserably because they have no idea what they are doing.

The key phrase is ‘deliberate practice’, not ‘going through the motions whilst clock watching’. Something which was proven by Robert Duke and his team at the University of Texas-Austin, who videotaped advanced piano students as they attempted to perform a technically challenging piece of music. There was no correlation between the standard of performance and how many times the students had practised the piece or even how many hours they spent practising in total. The only noticeable difference between the top ranked performers and everyone else was how they practised.

The super fingered players were able to identify their errors and correct them at the expense of time spent playing the parts which were easier to perform. At the beginning of the study, all players were of a similar standard and they all reported the same perceived difficulty in certain sections – but the better performers were able to improve at a faster rate by simply correcting their errors before moving on to the next part.

So you can see how this may seem to contradict the concept of interleaving, but in reality, they can combine to produce a highly effective studying routine.

Putting everything together to create a supercharged practice routine

Do you remember Boris, from up above? He’s back, with a vengeance.

As part of his interleaving practice session, which included an hour practising each of the previous two songs – Boris is now trying to learn ‘Master of Puppets’.

It seems straightforward enough, except the middle section contains a tricky arpeggio riff which is driving our little rock star insane. It’s fiddly, he’s not quite sure how to play it and his picking technique is a bit too sloppy anyway. So what should he do?

Let’s start by scaling it up (or down).

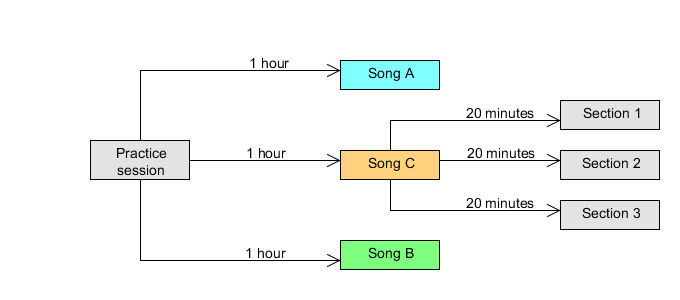

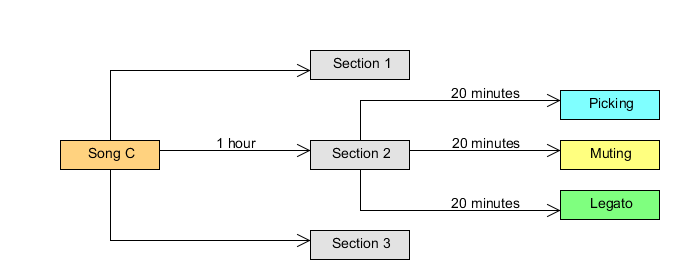

There are three songs – to save confusion, let’s call them song A, song B and song C.

Each song contains three sections of music – let’s call them section 1, section 2 and yep, you’ve guessed it… section 3.

So;

Song A – (sections 1, 2, 3)

Song B – (sections 1, 2, 3)

Song C – (sections 1, 2, 3)

The songs should be learnt using the interleaving approach to practising. This is because they are all sufficiently different to each other to provide a good selection of techniques, but ultimately they are all songs, and a song isn’t a skill – it’s a collection of skills.

The sections within each song should also be learnt using the interleaving approach, but if any section keeps throwing up errors or is too difficult to learn – then chunking should be employed until this part has been figured out.

The higher the scale – the more we should interleave our practice.

The smaller the scale – the more we should ‘chunk’ our practice.

So, to reiterate…

Boris has a three hour practice window – divided up equally between the three songs (interleaving).

Each song should be divided up into three equal parts – 20 minutes on section 1, 20 minutes on section 2 and 20 minutes on section 3 (interleaving).

He discovers that section 2 is too difficult, so in future he will lock into section 2 for the entire hour until he has grasped the technique (chunking).

Boris is still interleaving between the three songs but he is also spending more time on his weaknesses than his strengths (deliberate practice).

How low can you go?

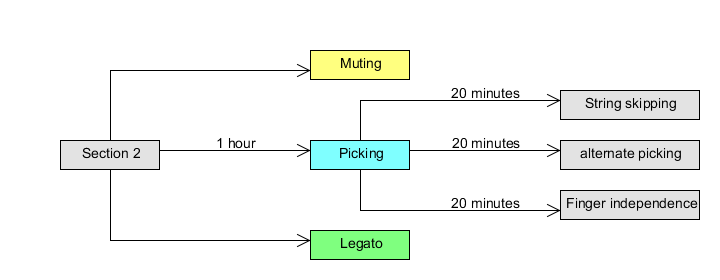

Any technique or skill can be broken down into smaller parts many times over. These building blocks can then be studied, put back together and built up over time to achieve the desired result.

We have three songs – song A, song B and song C.

Song C has three sections – section 1 (rhythm), section 2 (arpeggios) and section 3 (solo/rhythm).

Section 2 combines three main techniques – alternate picking, right hand muting and legato.

So using this example; Boris can even strip his 1 hour of deliberate section 2 ‘chunking’ into separate 20 minute sections focusing on these individual techniques. It could be the case that his main weakness could be alternate picking, which in turn affects the other two core techniques which make up section 2.

As you can see; there are numerous possibilities here, and you can stretch this method out as much as you want. It works with absolutely everything – from breaking down picking exercises, learning different sections of a song and even when studying scales, modes and other aspects of music theory.

Next time you plan out a practice session – give it a go. Break down the focus of your session into three equal parts and then, if you have enough time, subdivide each part again into three parts.

If and when you discover a section or a technique which is giving you a lot of hassle – that’s the ideal time to subdivide it again and tackle it in smaller chunks.

Have a go and let me know how you get on in the comments below.

If you have any questions – or if something isn’t clear, let me know and I’ll get back to you as quick as I can.

Leave a Reply